In the modern era of education, students and teachers are more connected globally than ever before, making internationalisation a key driver in Vocational Education and Training (VET).

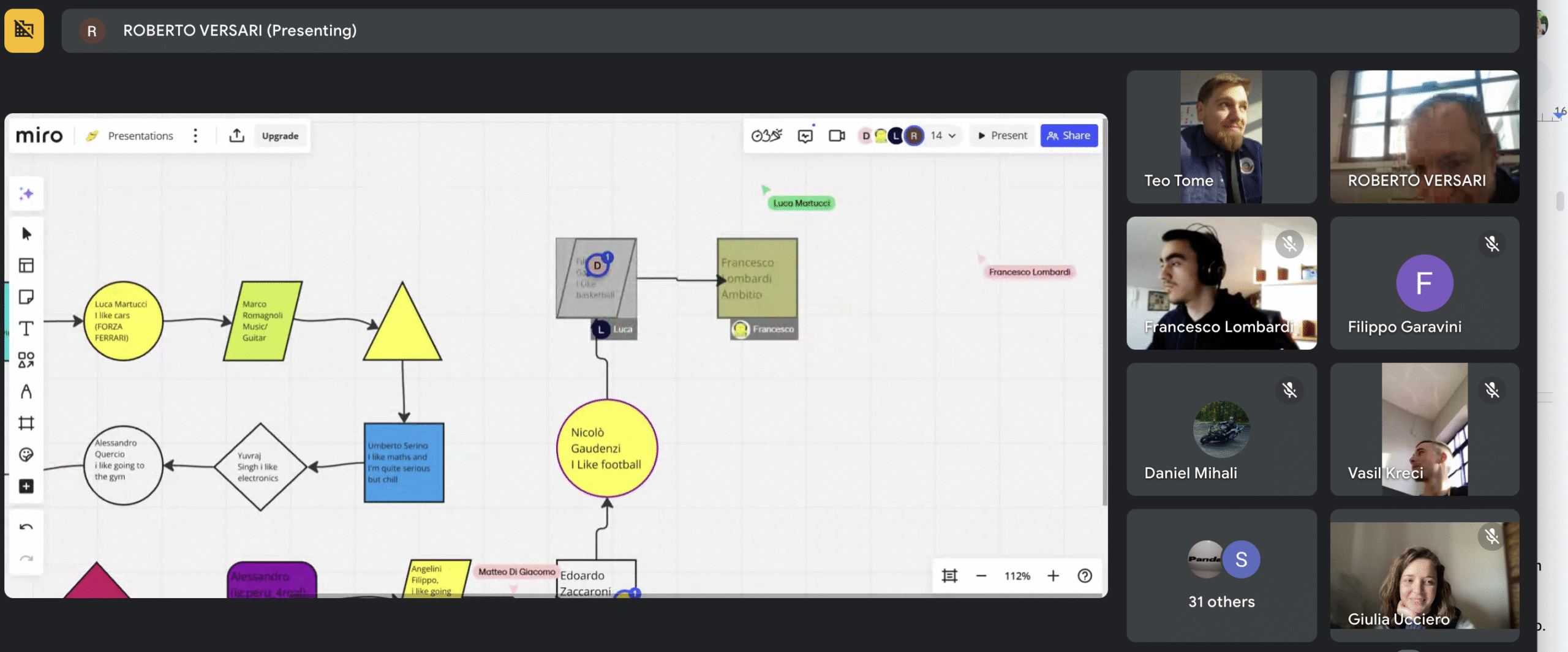

Following the COVID-19 crisis, the European Commission promoted virtual mobility and, in 2021, officially introduced blended mobility in the new Erasmus Plus Guidelines, defining it as: “Any study period or traineeship abroad of any duration may be carried out as a blended mobility. Blended mobility is a combination of physical mobility with a virtual component facilitating a collaborative online learning exchange and teamwork“.

Within this framework, one of the main aims of the Developing Capacity for VET Systems in Western Balkans (DC-VET WB) Erasmus+ project is to boost internationalisation strategies of VET schools across the Western Balkans.

To achieve this objective, this capacity building project, involving seven partners organisations from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Finland, Italy, Kosovo, Spain and Montenegro, developed an E-learning course on internationalisation for VET staff which has been tested among Western Balkans VET schools.

Meanwhile, DC-VET WB partners identified seven VET schools to be involved in piloting of three blended mobility projects focused on relevant and common topics:

- IT & automation

- Green energies

- Transversal skills

The implementation of the experimental mobilities took place from November 2024 until May 2025 with five days of physical mobility in Albania with two students and an accompanying person from each country for the finalisation of their blended project from the 15th to the 19th of September 2025.

These step-by-step guidelines capture these three experiences, offering concrete insights and practical recommendations with the objective of inspiring and supporting other VET schools in developing and implementing their own blended mobility initiatives in the future.

The pilot experiences carried out within the DC VET project clearly demonstrate how blended mobility can enrich VET schools by integrating classroom learning with digital tools and international cooperation.

One of the strengths of the blended mobility format is its flexibility: projects can be adapted to different VET sectors, school priorities and schedules. From this experience it was highlighted that a few hours spent together in person can be worth several online sessions, underlining the importance of combining both dimensions effectively.

Teachers agreed that blended mobility projects have a deep impact on students’ learning and growth. One teacher reflected that: “It was inspiring to collaborate with people from different cultural and educational backgrounds, to see how diverse perspectives could come together to solve problems, share knowledge, and create new ideas.” From the students’ perspective, the mobilities were described as rewarding, inspiring and fun: they improved competences, encouraged intercultural exchange and created lasting memories. As one student wrote: “I will encourage others to participate in projects like this if they get an opportunity because it was a good experience and I learned a lot (…). I would definitely do this again.”

These results confirm that blended mobility is not only a response to the challenges of recent years, but a sustainable and innovative approach to internationalisation. By combining digital and physical activities, schools can increase inclusiveness and extend international opportunities and competences to a wider group of learners and teachers.

| GOOD PRACTICE FROM DC VET PROJECT

If you would like to use the template piloted in DC VET project, you can download it here: Blended Mobility Journal Template. Finally, here you can see all the steps and activities carried out from the 3 pilot groups: |

In the modern era of education, students and teachers are more connected globally than ever before, making internationalisation a key driver in Vocational Education and Training (VET).

Following the COVID-19 crisis, the European Commission promoted virtual mobility and, in 2021, officially introduced blended mobility in the new Erasmus Plus Guidelines, defining it as: “Any study period or traineeship abroad of any duration may be carried out as a blended mobility. Blended mobility is a combination of physical mobility with a virtual component facilitating a collaborative online learning exchange and teamwork“.

Within this framework, one of the main aims of the Developing Capacity for VET Systems in Western Balkans (DC-VET WB) Erasmus+ project is to boost internationalisation strategies of VET schools across the Western Balkans.

To achieve this objective, this capacity building project, involving seven partners organisations from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Finland, Italy, Kosovo, Spain and Montenegro, developed an E-learning course on internationalisation for VET staff which has been tested among Western Balkans VET schools.

Meanwhile, DC-VET WB partners identified seven VET schools to be involved in piloting of three blended mobility projects focused on relevant and common topics:

- IT & automation

- Green energies

- Transversal skills

The implementation of the experimental mobilities took place from November 2024 until May 2025 with five days of physical mobility in Albania with two students and an accompanying person from each country for the finalisation of their blended project from the 15th to the 19th of September 2025.

These step-by-step guidelines capture these three experiences, offering concrete insights and practical recommendations with the objective of inspiring and supporting other VET schools in developing and implementing their own blended mobility initiatives in the future.

The pilot experiences carried out within the DC VET project clearly demonstrate how blended mobility can enrich VET schools by integrating classroom learning with digital tools and international cooperation.

One of the strengths of the blended mobility format is its flexibility: projects can be adapted to different VET sectors, school priorities and schedules. From this experience it was highlighted that a few hours spent together in person can be worth several online sessions, underlining the importance of combining both dimensions effectively.

Teachers agreed that blended mobility projects have a deep impact on students’ learning and growth. One teacher reflected that: “It was inspiring to collaborate with people from different cultural and educational backgrounds, to see how diverse perspectives could come together to solve problems, share knowledge, and create new ideas.” From the students’ perspective, the mobilities were described as rewarding, inspiring and fun: they improved competences, encouraged intercultural exchange and created lasting memories. As one student wrote: “I will encourage others to participate in projects like this if they get an opportunity because it was a good experience and I learned a lot (…). I would definitely do this again.”

These results confirm that blended mobility is not only a response to the challenges of recent years, but a sustainable and innovative approach to internationalisation. By combining digital and physical activities, schools can increase inclusiveness and extend international opportunities and competences to a wider group of learners and teachers.

| GOOD PRACTICE FROM DC VET PROJECT

If you would like to use the template piloted in DC VET project, you can download it here: Blended Mobility Journal Template. Finally, here you can see all the steps and activities carried out from the 3 pilot groups: |